Ironwood apa'apai (1884.98.50)

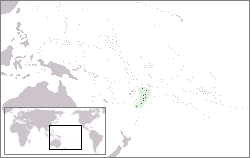

TongaIronwood apa'apai from Tonga, Oceania. Part of the Pitt Rivers Museum Founding Collection. Given to the Museum in 1884.

TongaIronwood apa'apai from Tonga, Oceania. Part of the Pitt Rivers Museum Founding Collection. Given to the Museum in 1884.

This is the second Tongan apa'apai to be featured in this gallery, although this example has a flat, diamond-section head and finished wood-carved decoration. Ergonomically and artistically, these weapons are among the simplest and most refined of the Tongan club forms, generally of medium length and moderately decorated.

The shape of an apa'apai is said to represent the flexible and fibrous coconut stalk. Indeed, whilst war clubs such as this one were made from a local casuarina, one of the hardest timbers in the world, coconut-leaf clubs were used to practice and perform feta'aki, the historical martial art and spectator sport of fencing.

The Art of War

The head and shaft of apa'apai were usually covered in elaborate carved bands of decoration featuring geometric shapes such as bars, chevrons, and triangles, but can also depict men, dogs, fish, turtles and birds. This surface decoration, known as tata, was unique to each club, granting it an individual identity and certain supernatural powers. In recognition of these qualities, a Tongan warrior would typically give his club a name.

Tongan clubs were carved by a number of different men, and it would have been unusual for any one weapon to be the sole product of a single craftsman. These craftsmen were known as tufunga tata and they were also responsible for the beautiful examples of woodcarving seen on Tongan houses and boats. Clubs were among the most complex and demanding of woodcarvings, despite the fact that the work required no lashing or jointing. The difficulty lay in the club's refined shape, which the carver was expected to match to pre-existing examples. There were more than sixty different types of club and each type conformed to a refined system of rules, defining the proportions of its dimensions, the curvature of its lines, the form and number of its collars, the kind of decoration appropriate to its type, and so on. Many of these formal conventions were encoded by using a unique West Polynesian technique of dividing strings to create spatial relationships between the weapon's dimensions, using complex fractions, mathematical squares, and so on. The designs would then be created in large, clearly demarcated zones using small tools made of marko shark teeth hafted onto a short handle, suitable for gouging out the shallow and complex patterns.